What is tribal sovereignty?

There are three types of sovereign governments in the United States: the federal government, state governments, and tribal governments. Tribal sovereignty refers to the inherent authority of tribal nations to self-govern, including the authority to establish their own form of government, determine citizenship, preserve cultural identity, and make and enforce laws.

There are currently 574 federally recognized tribal nations in the United States, including four Wabanaki Nations in Maine: the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, Mi’kmaq Nation, Passamaquoddy Tribe (at Motahkomikuk and Sipayik), and Penobscot Nation. Federal recognition means that the US government acknowledges tribes as sovereign governments, as well as its own “trust responsibility” to protect tribal land rights and natural resources, preserve tribal sovereignty and self-governance, and carry out legal mandates of federal Indian law.

Despite the recognition of tribal sovereignty in the Constitution, it wasn’t until the 1970s that the federal government began to take steps to support, rather than undermine, tribal self-governance. This followed more than four centuries of settler and colonial extermination, state-sanctioned genocide, and US government-directed efforts to forcibly remove, dispossess, assimilate, and terminate tribal nations. While the restoration of self-governance has proved critically important for tribes throughout Indian Country, unique provisions in federal and Maine law have led to the Wabanaki nations being left behind, unable to access the full benefits of their sovereign status.

Why is tribal sovereignty and self-governance important?

Sovereignty is an inherent right of Indigenous governments

- Tribal governments predate the sovereignty of the United States by thousands of years and derive their sovereign power from their people and connection to ancestral territory. Sovereignty is not a power given or taken away by an external government.

- Lands historically inhabited and utilized by Indigenous people were not “discovered” by Europeans. They were discovered by Indigenous people.

- Tribal sovereignty is confirmed in treaties, the US Constitution, Supreme Court decisions, and by the United Nations.

Self-governance preserves Indigenous cultures, languages, and resources

- The values, culture, and needs of tribal communities are best understood by tribal governments. Strong tribal governance systems also lead to better tribal-state cooperation.

- Self-governance results in tribes devoting greater resources to shared infrastructure and improved environmental and resource management.

- Only 170 of more than 300 Indigenous languages spoken in the US remain. Without restoration efforts, most of those will be lost by 2050. Sovereignty and self-governance help preserve language education, and oral traditions also help preserve tribal sovereignty.

Self-governance spurs economic growth for tribes and their neighbors

- Since colonization, the restoration of tribal self-governance in Indian Country is shown to be the only policy to produce positive economic outcomes for Native people. Widespread implementation of self-determination policy in the late 1980s saw per capita income on self-governing reservations grow three and a half times faster than the US as a whole, and poverty cut almost in half.

- Tribal governments that provide municipal services and infrastructure and diversify their economies often become economic drivers of their regions. Collectively, tribal governments directly support an estimated workforce of 350,000 as well as an additional 600,000 indirect jobs, $40 billion per year in wages and benefits, and an additional $9 billion spillover impact in state and regional economies.

Why doesn’t Maine recognize the sovereignty of the Wabanaki Nations?

In the 1970s, the Passamaquoddy Tribe asserted (and federal courts affirmed) that the US government was bound by its trust responsibility to protect Wabanaki land rights illegally claimed and sold by the state of Maine. Maine’s claim to the tribal land – amounting to almost two thirds of the state – was ruled invalid because the tribal land transfers and sales were never approved by Congress. That ruling set up a pair of unprecedented land-claim suits filed by the US Department of Justice on behalf of the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation against the State of Maine. After four years of negotiations aimed at resolving the dispute out of court, and with the tribes facing intense public and political pressure to accept an agreement, the federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA) and the state Maine Implementing Act (MIA) were ratified in 1980.

Collectively known as the Settlement Acts, MICSA and MIA required the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation to give up claim to their dispossessed lands in exchange for a federally funded pathway to buy back just 2.5 percent of the 12 million acres unlawfully claimed by Maine. Congress enacted separate federal laws to address similar claims brought by the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians and the Mi’kmaq Nation. The Settlement Acts allow Maine to exert an unusual level of jurisdiction over tribal affairs not found in any other state. Running in stark contrast to federal Self-Determination Policy evolving at that time, the interpretation of this regressive and paternalistic element of the settlement has been disputed ever since. For more than 40 years, the state of Maine has used the Settlement Acts to deny Wabanaki Nations’ sovereignty and authority to self-govern, a position in direct conflict with the inherent sovereign rights of all federally recognized tribal nations and the foundations of Federal Indian Law.

How does the denial of tribal sovereignty impact Wabanaki citizens and all Mainers?

Wabanaki Nations are blocked from accessing many benefits of federal Indian laws

- Unless Wabanaki Nations are explicitly named in a federal Indian law, those laws are blocked in Maine if they “affect or preempt” Maine’s jurisdiction. Since 1980, Congress has enacted over 151 federal laws for the benefit of tribal nations. Maine has fought to block Wabanaki access to many of them, including those that address public safety, health care, and environmental quality.

- Only one federal law, the Violence Against Women Act, has been successfully extended to the Wabanaki since the Settlement Acts passed – a full 17 years after provisions protecting Indigenous women were included.

- The cost and failure rate associated with fighting for inclusion in federal Indian laws discourages the Wabanaki from hiring and investing in new programs, resulting in a cycle of underdevelopment of tribal governments that leads to stunted economic growth in the Wabanaki Nations as well as their surrounding rural communities.

Economic growth is severely restricted for Wabanaki nations and surrounding communities

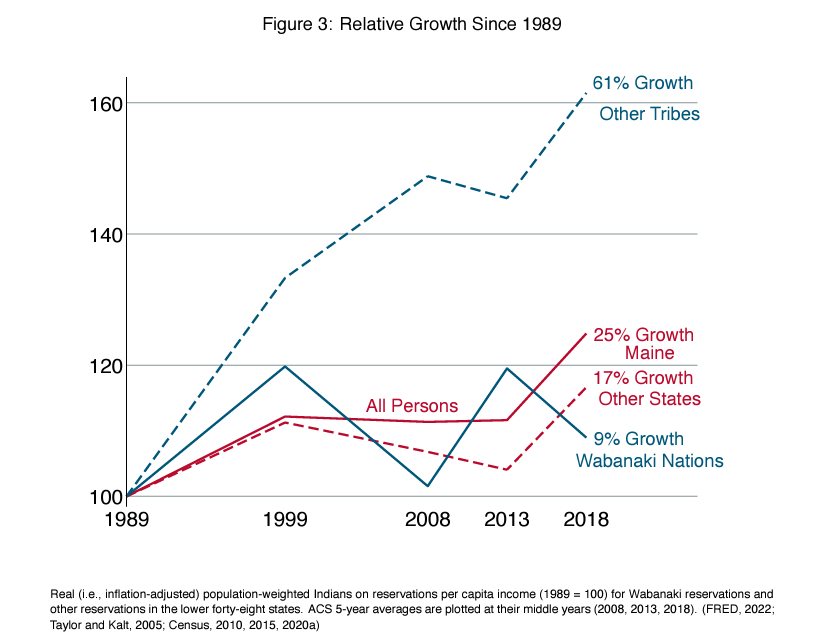

Chart from research report “Economic and Social Impacts of Restrictions on the Applicability of Federal Indian Policies to the Wabanaki Nations in Maine” by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, December 2022

- Compared to tribes outside of Maine, all four Wabanaki Nations lag severely in economic development, even when adjusting for the tribes’ size and rural location. Since 1989, income growth for the Wabanaki Nations has been consistently below that of other tribes and of Maine more broadly. Economic growth in Maine does not extend into tribal communities as it does in other states.

- Even while income in Maine grew faster than the national average, Wabanaki income grew far slower. Between 1989 and 2018, income in Maine grew 25%, far better than the 17% growth in the US as a whole. But for Wabanaki citizens, income growth was just 9%.

- In 2021, the average income for Mainers was more than twice as high as Wabanaki citizens’. Compared to the rest of Maine, the Wabanaki child poverty rate is almost four times higher.

- Researchers estimate that restoring self-governance capabilities for the Wabanaki Nations would result in the direct and indirect addition of more than 2,700 new jobs – 85% of which would be gained by non-tribal citizens. It would also add an estimated $330 million each year to Maine’s GDP, with the benefits of this growth concentrated in rural and economically deprived portions of Aroostook, Penobscot, and Washington counties.

The Settlement Acts are widely regarded as a failure

- Four decades later, neither Passamaquoddy nor Penobscot Nations have been able to acquire land promised to them, the laws have been unevenly applied among the tribes, legal disputes persist, tribal-state relations remain contentious, and economic prosperity for both tribal and non-tribal citizens is stunted.

- Beyond the Maine Indian Tribal State Commission, created through the settlement as a structure for evaluating its effectiveness, multiple task forces, resolves, reports, and work groups have all recommended substantive changes to the settlement over the decades, but only the state (unlike the tribes) is empowered to enact them. With legislative, executive, and judicial systems weighted entirely towards the benefit of the state, recommendations are consistently rejected.

What is being done to restore recognition of Wabanaki Nations’ sovereignty?

Widespread bipartisan support for restoring recognition of Wabanaki sovereignty continues to grow in Maine. In 2020, a bipartisan task force issued 22 consensus recommendations to modernize the Settlement Acts and restore self-governance over a range of issues, including criminal justice, natural resource management, gaming, taxation, and land acquisition. These recommendations formed the basis of state legislation in 2022 and 2023 that received strong bipartisan approval in the legislature but were ultimately blocked by Governor Mills’ opposition. In Congress, legislation sponsored by Rep. Jared Golden that would have extended the benefits of federal Indian laws to the Wabanaki nations failed to advance in the Senate following opposition from Sen. Angus King.

In 2024, bills that would have created an office of tribal-state affairs, a Wabanaki studies advisory council, and a commission to review state lands and waterways with sacred or traditional significance to the Wabanaki people, and allowed the Mi’kmaq Nation to receive sales tax revenue for sales occurring on tribal land passed in the legislature but ultimately were left to die on the appropriations table. However, legislation that expands tribal court jurisdiction was signed into law. While the law enacts several of the task force’s recommendations, efforts to address remaining concerns will continue in the next legislative session.

Wabanaki Sovereignty Timeline

North American event dates are in black, Wabanaki-specific event dates are in blue.

Choose an era:

21,000 BCE – Scientific research confirms humans living in North America up to 23,000 years ago.

11,000 BCE – Tools and artifacts found near Aziscohos Lake (near what is now known as Rangely) show Wabanaki ancestors living there as long as 13,000 years ago. Family bands of nomadic hunters and gatherers collect shellfish on the coast, fish salmon in the rivers, and hunt moose in the interior forests.

1000 – Viking ships visit the Mi’kmaq people in what is now known as the Canadian Maritimes. The northeastern region known as Waponahkik, or “Dawnland” – includes areas now known as New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Maine. Trade networks and family ties connect Wabanaki communities including Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki tribes.

1452 – 1493 – The Vatican issues a series of papal decrees authorizing colonization and justifying the enslavement of Native people found in newly explored lands. These decrees form the basis of the “Doctrine of Discovery” that leads to the subjugation, dispossession, forced conversion, enslavement, and cultural genocide of millions of people on five continents. Later popes attempt to renounce the doctrine, but their efforts are largely ignored. Doctrine of Discovery arguments are cited in US law as recently as 2005.

1492 – Explorer Christopher Columbus, commissioned by Spain, lands in the Bahamas and begins enslaving the Native Taíno people. His arrival sets off a fierce rivalry among European powers for land and resources and unleashes deadly epidemics estimated to have caused 56 million deaths by 1600 – a population loss of 90% in the Americas.

1524 – Explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, commissioned by France, encounters Wabanaki people along the coast of what is now Maine. Other explorers in the area during this time kidnap and enslave Wabanaki people, and European fishermen plunder once-plentiful cod to near extinction.

1616 – 1619 – By the time European settlements are established in the early 1600s, Wabanaki timber, fur, and fishing resources are ravaged. More than 75% of the tens of thousands of Wabanaki people die from disease in this period called The Great Dying.

1621 – British settlers at Plymouth Colony are first greeted by Samoset, an Abenaki chief from the area now known as Maine. He welcomes them in English, learned by talking to fishermen working the waters around Monhegan Island.

1621 – The Wampanoag people form an uneasy alliance with British settlers at Plymouth Colony in what is now referred to as the first Thanksgiving.

1675 – 1760 – In multiple wars, known to English settlers as the French and Indian Wars, rival European and Native people battle for control of land and resources for nearly a century. Entire settlements – both Native and European – are wiped out. In 1705, colonies begin adopting blood quantum laws that limit civil and land rights of Native people and Africans. People determined to be less than 50% Native could be stripped of their land rights.

1675 – 1755 As the English and French fight for control of the Northeast and its resources, the Wabanaki are caught in the middle and struggle to maintain their territory. Trade and farming are disrupted, and many Wabanaki starve. Wabanaki tribes form a political alliance called the Wabanaki Confederacy. In 1724, British forces attack a French mission in Norridgewock, killing between 80 and 100 Wabanaki men, women, and children along with the French Catholic priest, forcing the rest to flee to Quebec.

1755 – The Governor of the Massachusetts Colony issues a bounty for the scalps of Penobscot men, women, and children, and requires colonists to “embrace all Opportunities of pursuing, captivating, killing and destroying all” Penobscot people. The following year, the Governor of Nova Scotia renewed a similar bounty for Mi’kmaq scalps that was never rescinded.

1763 – The treaty marking the end the French and Indian Wars does not include Native signatories but results in the British taking control of large expanses of North American territory, including unceded Native lands. Britain’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 aims to control colonists’ westward migration and prevent costly wars with tribes by defining a large Indian Reserve west of the Appalachian Mountains off-limits to colonists. The proclamation inflames colonists and is included among their grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence.

1775 – American Revolutionary War begins. Tribal nations are divided and forced to pick a side, often swayed by promises of protected land rights.

1775 – After General George Washington requests their assistance, the Passamaquoddy join the fight against the British. The Penobscot Nation also sends warriors to aid the Americans after receiving assurances that white encroachments on their land would be addressed.

1776 – Immediately following the Declaration of Independence, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet tribes sign the Treaty of Watertown, the first international treaty negotiated with foreign nations by the United States of America. Letters to and from George Washington affirm the extension of the peace and friendship agreement to the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes. The treaty establishes friendly government to government relations, pledges mutual aid and assistance in the battle with Britian, and acknowledges the parties as brothers, military allies, and economic co-equals under international law. The treaty remains in effect today.

1783 – The Treaty of Paris, marking the end of the American Revolution, does not include Native signatories and results in the US government taking control of most North American territory – including unceded Native land, and creating international borders that divide tribal lands and families. It voids Britain’s Indian Reserve to enable westward American expansion.

1788 – The US Constitution asserts Congress has the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, states, and tribes. It also asserts the constitution, laws, and treaties made by the US government are the “supreme Law of the Land.”

1790 – The Trade and Non-Intercourse Act declares only the federal government has the authority to make treaties or purchase land from tribal nations. This law forms the basis of the 1972 Maine Indian Land Claims suit against the State of Maine.

1794 – The Passamaquoddy Tribe signs the Treaty of 1794 with Massachusetts, greatly reducing their territorial boundaries. Language barriers, dishonest brokers, and cultural differences about concepts of land use and ownership result in wildly different interpretations of deals that are almost always confirmed in favor of white parties by white legal systems. The treaty is never ratified by Congress, as required by the 1790 Trade and Non-Intercourse Act, and later becomes the basis for a sweeping land claims suit against the State of Maine.

1796 – 1818 By the beginning of the 19th century, Wabanaki populations have been reduced by disease, war, and starvation from an estimated 15,000 in 1600 to less than 800 in the 1800s. The Penobscot Nation signs two treaties with Massachusetts, relinquishing vast tracts of tribal land on both sides of the Penobscot River in exchange for $400, blankets, clothing, and food. The treaty is never ratified by Congress, in violation of the 1790 Trade and Non-Intercourse Act.

1803 – The Louisiana Purchase outlines the terms for the US to purchase from France 830,000 square miles of territory ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Tribal nations within Louisiana’s boundaries are not included in the negotiations, despite the territory including unceded Native land. The following year, the Lewis & Clark expedition charts western North America, encouraging a new wave of white incursion on Native land.

1820 – Maine becomes a state under the Missouri Compromise and assumes all treaty obligations from Massachusetts. Maine places Wabanaki people under legal guardianship and designates government agents to manage tribal affairs, money, and resources. “Indian agents” give Native families a weekly allowance to buy food and necessities. Spending for reservation projects requires the agent’s approval. In its second year, the Maine legislature bans interracial marriage. The law remains intact until 1883.

1821 to 1842 – As the lucrative timber industry booms, Maine authorizes multiple land seizures, sales, leases, and timber harvests from Passamaquoddy land without tribal permission, in violation of the 1794 treaty. In 1833, Maine seizes four Penobscot townships, representing 100,000 acres and 95% of Penobscot treaty land. Maine holds all proceeds of the illegal land sales and usage and determines how and when funds are spent. Prevented from accessing traditional sources of food and trade, and with community structures replaced by state monitors, the tribes struggle to survive.

1823 – The Penobscot Nation sends a Representative to the state Legislature. Maine is the only state to include tribal representatives in its Legislature. The Passamaquoddy Tribe sends its own in 1842. Tribal Representatives are permitted to speak on the floor, but not to vote.

1823 – 1832 The Marshall Trilogy of US Supreme Court rulings create the foundation for current Federal Indian Law. The rulings establish the federal government’s “trust responsibility” – the moral obligations the US must meet to ensure the protection of Native lands, assets, resources, and sovereign rights. The rulings also clarify the nation-within-a-nation framework, exclude state law from Indian Country, and recognize tribal governance authority. While providing guidance about interpreting treaties in favor of tribes in the face of ambiguity, the rulings also determine tribes to be “domestic dependent nations” and uses “Doctrine of Discovery” arguments to reduce the right of Indigenous people to their ancestral lands to a mere right of occupancy.

1824 – Congress creates the Bureau of Indian Affairs, initially under the Department of War. One of its functions is to administer funds to churches and missionaries to “civilize” Native people by teaching Native children to replace tribal practices with Christian practices.

1829 – President Andrew Jackson, preparing for mass removals of Indigenous people from their homelands, advocates placing Passamaquoddy land in trust, in recognition that the tribe “fought with us for the liberty we now enjoy.”

1830 – The Indian Removal Act authorizes the forced removal of Indigenous people from their ancestral lands to free up lucrative farmland for white settlement. An estimated 100,000 Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole people are forced to abandon their homes and relocate to “Indian Territory” in what is now known as Oklahoma. An estimated 15,000 died on the journey. The removal of the Cherokee people is remembered as the Trail of Tears.

1842 –The Webster-Ashburn Treaty defines the northern US border in Maine, and in the process, divides Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy tribal land between two countries, without including the tribes in negotiations. That same year, the Maine Supreme Court finds in Murch v. Tomer that “Imbecility on [the Indians’] part, and the dictates of humanity on ours have necessarily prescribed to them their subjection to our paternal control; in disregard of some, at least of abstract principles of the rights of man.”

1850 – The new state of California authorizes forced indentured servitude for Native people, funds efforts to eradicate them from the state, and allows white people to take custody of Native children, leading to an active child slave trade. The Native population in California drops from 150,000 in 1850 to just 30,000 two decades later. By 1900, only 16,000 Native people remain in California.

1854 – 1890 The Plains Wars in the west overlap with the Civil War (1861 – 1865) in the east. The gold rush, railroad expansion, bison decimation, broken treaties, and settlers drawn by a promise of free land all serve to inflame tensions and spread open conflict between white people and tribes in the Great Plains. By 1890, tribes are hemmed into reservations a fraction of their original size, once vast bison herds near extinction, and tribal military power is shattered.

1867 – The Treaty of Cession outlines the terms for the United States to purchase Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million. Alaska Native people are not part of the treaty negotiations and object to the sale of their land.

1873 – Maine legislature removes treaty obligation language from printed Constitution.

1879 – 1926 To extinguish tribal culture, Native children as young as four are abducted from their families and sent to military-style Indian boarding schools run by the US government and churches. Prohibited from speaking Native languages and engaging in cultural practices, and stripped of traditional clothing, hair, and belongings, they suffer physical, sexual, emotional, and cultural abuse. Many die in residence. By 1926, an estimated 83% of Native school-age children are attending boarding schools.

1879 – Many Wabanaki children are taken from their families and sent to Indian boarding schools, including 44 Penobscot and 8 Passamaquoddy children sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the first government-run Indigenous boarding school. Carlisle’s founder was blunt about the school’s purpose: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” 189 children from more than three dozen tribal nations are buried in the Carlisle school cemetery. Passamaquoddy children were also sent to the Genoa Indian Industrial School in Nebraska. Between 1928 and 1967, Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, and Passamaquoddy children are taken to the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia.

1883 – The Code of Indian Offenses punishes Native dances and rituals by imprisonment or withholding food for 30 days. “Medicine men” who encourage others to follow traditional practices are imprisoned until they can prove they have abandoned their beliefs. In 1890, the US government slaughters more than 200 Sioux men, women, and children gathered to perform the Ghost Dance at Wounded Knee.

1887 – The General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) allows the federal government to break up tribal lands and communities into standardized individual allotments which can be sold or given to non-Natives. “Surplus” land is sold and removed from tribal holdings. Christian churches operating on reservations are allowed to keep tribal land. The move and subsequent laws fraction tribal communities into checkerboards of unconnected parcels and results in the loss of 90 million acres of tribal land.

1892 – In a case that sought to define whether Maine’s hunting laws applied to Native people on their own land, State v. Newell ran contrary to Federal law by finding tribes are fully subject to state law.

1912 – Maine outlaws salmon spear-fishing, an important traditional hunting practice for the Wabanaki.

1918 – More than 12,000 Native Americans serve in World War I, most as volunteers. While Native people are often prohibited from speaking tribal languages back home, those languages prove invaluable for sending secure messages in war.

1918 – Many Wabanaki serve in the US and Canadian forces during World War I, including a quarter of all Passamaquoddy men. Some are killed in action, including the son of Passamaquoddy Governor William Neptune, and Charles Lola, posthumously awarded France’s Croix de Guerre for his bravery in battle. Almost 100 years pass before the United States recognizes their service.

1924 – The Indian Citizenship Act grants US citizenship to all Native people born in the US. Some tribes reject citizenship, believing it implies a ceding of tribal sovereignty and land rights. The right to vote is governed by state law. It takes another 38 years before Native people in all 50 states can vote.

1924 – Before passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, members of the Passamaquoddy Tribe petition Maine’s governor against extending US citizenship to their tribe, like some tribes in other parts of the country. Despite the federal government applying US citizenship to Native Americans, Native people in Maine are denied the right to vote.

1934 – After a devasting report revealed the government’s failure in its trust responsibility to protect Native people and their land, culture, and resources, the government changes course. The Indian Reorganization Act stems tribal land loss by ending land allotments, prohibiting the removal of land without tribal consent, and allowing the addition of new trust land for new reservations. It also recognizes tribal governments and promotes (US-style) self-governance.

1935 – A report from the US Bureau of Indian Affairs finds state negligence in providing health services for Passamaquoddy people. Typhoid, pneumonia, and tuberculosis are common, fueled by impure water sources. Malnutrition is rampant and 20 tribal members die this year.

1941 – After an effort to secure equal privileges for tribal Representatives in the State Legislature failed, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Representatives are ejected from the Maine Legislature. Their seats are not restored until 1975.

1941 – 1945 – During World War II, more than 44,000 Indigenous people serve, enlisting at the highest rate of any group. Among some tribes, as many as 70% of eligible men served. Native language skills are utilized by “code talkers” whose unbreakable messages prove pivotal in several battles.

1941 – 1945 People representing all four Wabanaki Nations served in World War II, including some who served as “code talkers.” One of 84 Penobscot men and women who served in the war, Charles Shay later receives France’s highest military and civilian honor for his heroic actions on D-Day.

1942 – Transcripts show Maine legislators and Attorney General admitting to a legacy of defrauding Wabanaki Nations, ignoring treaty obligations, and advancing assimilation efforts to take back Native land, reduce tribal membership, and ultimately eliminate the tribes.

1950 – The US government’s Termination Policy establishes the intent to eliminate all Native tribes, solving the “Indian problem” and gaining valuable land and resources. Coercive efforts draw people off reservations and extinguish the legal sovereignty of tribal nations one by one. In less than a decade, the federal government terminates 109 tribes. 12,000 Indigenous people lose their tribal affiliation, 2.5 million acres of tribal trust land is sold to non-Natives, and jurisdiction is turned over to states.

1954 – A state constitutional amendment explicitly gives Indigenous people in Maine the right to vote in federal elections, one of the last states to do so. Indigenous citizens living on reservations are still prohibited from voting in state and local elections.

1956 – The Indian Relocation Act aims to further assimilate and reduce Native land holdings on reservations by encouraging Indigenous people to relocate to cities. 100,000 people leave reservations as part of the government program. Today, more than two thirds of Indigenous people in the US live in cities, not on reservations.

1958 – The Indian Adoption Project, which places Native children with white families, replaces boarding schools as a more cost-effective tool for assimilation and cultural extinction over the next 20 years. In the 1960s, a quarter of Native children live apart from their families.

1967 – Indigenous people in Maine permitted to vote in state and local elections.

1968 – The Indian Civil Rights Act provides tribal citizens with similar, but not identical protections as the US Constitution.

1968 – The Passamaquoddy Tribe begins its land claims case, arguing the Tribe is owed at least $150 million in mismanaged trust funds and title to tens of thousands of acres of illegally sold land. Seeking to derail the suit, state and local officials conspire to frame and oust the Tribe’s attorney. The case, in that form, dies. Decades later, Maine’s Governor issues a posthumous pardon.

1969 – Mi’kmaq and Maliseet people in Maine form the Association of Aroostook Indians to collectively advocate and seek federal recognition. Because their tribes exist on both sides of the US-Canadian border and lack officially reserved lands, the US government considers them “Canadian tribes.” In 1973, Maine recognizes both tribes, helping to pave the way for federal recognition.

1971 – The discovery of oil reserves in Alaska spurs the effort to settle land claims suits with Alaska Natives. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act extinguishes aboriginal land title and replaces it with 212 for-profit regional and village corporations, owned exclusively by Alaska Native shareholders, to manage 44 million acres of land.

1972 – Native activism flourishes with the formation of the American Indian Movement (AIM) which raises awareness of relocation’s failures, fights employment discrimination, defends treaty rights, and launches Native-run health, housing, legal support, and education projects in Minneapolis. The birth of the Red Power Movement and other civil rights activity push the US government to change course from termination to self-determination.

1974 – Report to the US Commission on Civil Rights finds “Maine Indians are being denied services provided other American Indians by various Federal agencies” and the denial “constitutes invidious discrimination.”

1975 – Between 1950 and 1975, more than 50,000 Indigenous people serve in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Of those who serve in Vietnam, more than 90% are volunteers.

1975 – The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act officially ends Termination policy and empowers tribes to exercise their sovereignty and control their own affairs, including the education of their children.

1975 – Passamaquoddy v. Morton holds the US government has a trust responsibility to the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation, and Maine’s claims to tribal land are invalid. The tribes receive federal recognition and authority over tribal affairs is transferred from state to federal government. The federal government files land claims suits against Maine on behalf of the tribes. Penobscot and Passamaquoddy Representatives are restored in the Maine Legislature.

1978 – The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) creates a stricter standard for removing Native children from their families, to help Native people maintain cultural and linguistic ties to their tribes and stem Native displacement. While considered the gold standard of child welfare law, today Native children continue to be removed from their families at higher rates. Congress also creates a process for tribes to receive federal recognition and enacts the American Indian Religious Freedom Act recognizing and protecting Indigenous people’s inherent right to exercise their traditional spiritual practices.

1979 – State v. Dana holds state criminal laws are not applicable to Indians on Indian land in Maine and Indian land in Maine is “Indian Country” under federal law. Bottomly v. Passamaquoddy Tribe holds tribes in Maine retain the full attributes of sovereignty as defined by Federal Indian Law.

1980 – Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA) and Maine Implementing Act (MIA) settle the land claims suit brought by the federal government against Maine on behalf of the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation. The Aroostook Band of Maliseet Indians is also included and receives federal recognition that year. The tribes give up claim to disposed lands in exchange for a federally funded pathway to buy back a small fraction of their land. The Maliseet receive federal funding enabling them to create an official reservation in Houlton. Provisions allow Maine to exert an unusual level of control over tribal affairs not found in any other state, and even exert complete jurisdictional authority over the Mi’kmaq Nation, which was not included in settlement negotiations. As a result, landmark federal court rulings and laws of the 1980s that expand tribal self-governance can’t apply to tribes in Maine.

1980 – 1990 Court rulings affirm tribal sovereignty over most issues occurring on tribal land. Regional and resource-based intertribal partnerships form. In 1988, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act ushers in a new era of economic development.

1989 – Objecting to terms that put its land under state jurisdiction, the Mi’kmaq Nation refuses to ratify the Micmac Settlement Act. Although the Mi’kmaq Nation (then known as the Aroostook Band of Micmacs) receives federal recognition and funding to purchase trust land in 1991, the lack of a consolidated reservation combined with the state’s assumption of its own overarching authority through the Settlement Acts leaves the Nation in jurisdictional limbo for decades, unable to build tribal government infrastructure or benefit from federal recognition. Because blood quantum and US birth are used to determine tribal citizenship, Mi’kmaq family who relocate to Maine from Canada are excluded from tribal membership, dividing families.

2000 – 2022 Multiple efforts to remedy the tribal land loss and fractionation caused by earlier allotment policies results in the Indian Land Consolidation Program and the Land Buy-Back Program. Both programs offer federally funded pathways for tribes to reacquire land but are sorely underfunded.

2001 – Wabanaki history becomes a required subject in state schools. More than two decades later, a report finds the state fails to consistently and appropriately apply the law in schools.

2005 – US Supreme Court cites the “Doctrine of Discovery”, the Vatican-sponsored justification for taking tribal land, in its decision denying the Oneida Nation the authority to reclaim its land.

2007 – United Nations adopts the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, affirming international recognition of tribal nations’ inherent sovereignty. The United States did not sign on in support until 2010, the last nation to do so.

2010 – Settling a class action lawsuit, the federal government creates a $1.5 billion fund to pay individual Indian trust beneficiaries, a $1.9 billion Trust Land Consolidation fund, and an Indian Education Scholarship Fund of up to $60 million.

2011 – Governor LePage’s Executive Order “Recognizing the Special Relationship Between the State of Maine and the Sovereign Native American Tribes Located Within the State of Maine,” requires the state to consult with the tribes on any law, rule, or policy that will significantly impact them. He rescinds it just four years later, prompting the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes to withdraw their legislative representatives in protest.

2012 – The Maine Indian State Tribal Commission issues a letter to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples stating: “The [Settlement] Acts have created structural inequities that have resulted in conditions that have risen to the level of human rights violations.” The first Representative from the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians is added to the Maine Legislature but is soon frustrated by the lack of voting authority. The Band stops seating representatives in 2018.

2015 – Maine-Wabanaki State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission finds Native children in Maine are still five times more likely than non-Native children to be removed from their families. Failure to identify children’s Native ancestry, institutional racism, historic trauma, and contested sovereignty all contribute to the commission’s findings of evidence of cultural genocide.

2016 – The Passamaquoddy Tribe’s representative returns to the state legislature. By 2019, the Passamaquoddy Tribe is the only Wabanaki Nation seating a representative. The Penobscot Nation and Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians currently appoint ambassadors to communicate with state and federal governments.

2019 – In McGirt v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court rules about half of Oklahoma is Native American land. Some of this victory is rolled back when the court narrows the decision to say the state has the authority to prosecute crimes by non-Indians committed on tribal land.

2019 – Following unsuccessful attempts to get Maine to recognize the Penobscot River as part of its reservation, the Penobscot Nation and federal Environmental Protection Agency force the state to adopt stricter water quality standards, making sustenance fishing possible after decades of paper industry pollution. Maine prohibits Native-themed mascots in schools, replaces Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day, and authorizes a task force to recommend changes to the Settlement Acts.

2020 – A report from the bipartisan commission established to evaluate the Settlement Acts issues 22 consensus recommendations for improving tribal-state relations and restoring self-governance. Wabanaki Nations in Maine join forces to form the Wabanaki Alliance to collectively advocate for tribal sovereignty and issues impacting Wabanaki people. A full 17 years after the federal Violence Against Women Act added provisions protecting Indigenous women, Maine allows the law to apply in Maine, giving tribal courts the authority to prosecute non-tribal people accused of committing domestic violence and other crimes against Native people on tribal land.

2022 – A report finds the 1980 Settlement Acts severely restrict economic growth of Wabanaki and neighboring communities. Legislation is passed opening gaming opportunities to Wabanaki Nations, but a broader bill based on the Settlement Act Task Force’s recommendations to restore tribal sovereignty stalls in the face of a veto threat.

2023 – The Vatican formally repudiates the “Doctrine of Discovery” used to justify nearly 500 years of theft of tribal land and subjugation of Indigenous people.

2023 – The Mi’kmaq Restoration Act brings the jurisdictional authority of the Mi’kmaq Nation in line with that of the other Wabanaki Nations in Maine, recognizing the Nation’s right to manage internal tribal affairs, create a tribal court, regulate natural resources, and create its own tax systems on tribal land. A bill that would change the Settlements Acts to ensure federal laws apply to Wabanaki Nations passes with bipartisan majorities in the Maine legislature but is vetoed by Governor Janet Mills. A similar federal bill fails to advance after opposition is voiced by Senator Angus King. Maine lawmakers and citizens vote to restore Maine’s treaty obligations to printed versions of the state constitution.

2024 – Jurisdiction over most criminal offenses occurring on tribal land are restored to Wabanaki tribal courts. Another new law requires Maine to notify Wabanaki Nations about any new law that affects the tribes or requires their certification. Other bills, including one creating an office of tribal-state affairs, die as a result of legislative disfunction.

MECEP wishes to acknowledge and thank the external reviewers who provided valuable time and insight:

Penobscot Nation Ambassador Maulian Bryant

Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians Ambassador Zeke Crofton-Macdonald

Mi’kmaq Nation Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Jenny Gaenzle

Michael-Corey Hinton, Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik

Passamaquoddy Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Donald Soctomah