As Congress move toward sweeping changes to SNAP, the federal food assistance program, U.S. Rep. Bruce Poliquin is touting Maine’s experiment in stricter eligibility as a model to be followed nationally.

The problem is that Maine’s approach has been a colossal failure. Its policy of work requirements resulted in more people going hungry without any demonstrable success in helping low-income Mainers secure stable employment.

Despite these outcomes, Maine Gov. Paul LePage and Rep. Poliquin have claimed the policy was a success, and the congressman has cited Maine’s experience to push for stricter work requirements in the House of Representatives’ version of the 2018 Farm Bill, which includes reauthorization for funding for food assistance.

The House proposal represents a huge change to SNAP — the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, more commonly known as “food stamps.” It would impose even more restrictive work requirements on SNAP beneficiaries, broaden the work requirements to cover parents in new ways, and impose mandatory employment and training programs for recipients.

Rep. Poliquin has learned the wrong lesson from Maine’s work requirements. Maine’s experience is not a model. If anything, a cautionary tale of policy gone wrong.

Work requirement policy didn’t work for Maine

In late 2014, Gov. LePage’s administration began imposing work requirements on all Mainers who got help paying for food from SNAP. The decision ended a longstanding state policy of waiving work requirements for Mainers in high-unemployment areas, where jobs were few and far between. Since this course reversal, 18- to 49-year-olds receiving food assistance have been required to be in work, education, training, or community service for at least 20 hours per week. Food assistance is cut after three months for those individuals who can’t prove they’re meeting the requirement, and they can be frozen out of assistance entirely for up to three years.

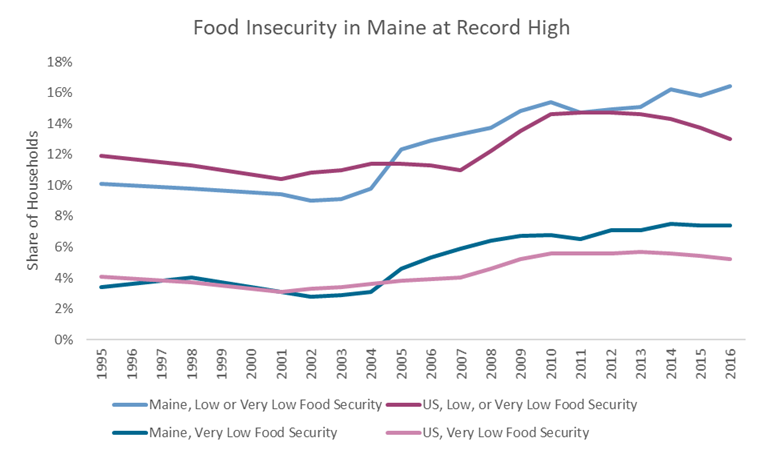

The results were immediate and dramatic. Roughly 10,000 Maine households lost food assistance in the first three months the new policy was in place. Over the next three years, roughly 40,000 Mainers were dropped from SNAP, but there’s no indication that fewer Mainers are going hungry. Since 2014, the share of Maine households that are food insecure has increased even as the share in the rest of the nation is declining. Most alarmingly, rates of “very low food security,” a condition in which a family regularly doesn’t have enough to eat, has increased to the point that Maine is statistically tied for the highest rate of hunger in the nation.

Source: MECEP Analysis of US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service data. Data were collected in 1995, 1996-98, and in three-year averages for 1999-2001 onwards.

Data reveals work requirements increased hardship for Mainers

Poliquin, LePage and others justify their praise for Maine’s experience with work requirements by citing an incomplete study of its effects conducted by the governor’s own Office of Policy and Management.

The report shows wage gains among a minority of those who lost food assistance in 2014 — a data point clung to by advocates of work requirements. However, the report’s other data are in line with what we know about the impact of work requirements from more thorough national research — namely that while work requirements produce a modest and temporary boost to hours worked and total earnings for a minority of the affected population, but that those results fade over time. In the end, most people affected by the policy are worse off than before.

Among the 5,000 SNAP recipients who lost access to food assistance in December of 2014:

- 42% didn’t work in the year prior to the policy change or the year following. The only impact the policy had on these 2,800 Mainers was to deprive them of food assistance when they had no income.

- 10% worked in the year before the policy change but didn’t work afterwards. These Mainers lost their jobs and had no safety net to fall back on.

- The number who were working a year after the change was slightly higher than before, but the report offers no evidence that the policy itself was responsible. During the period of the “study,” Maine’s overall economy improved, and all Mainers’ hours and total earnings increased on average.

- Both before and after the policy change, those who worked did not do so consistently. The data suggest that most individuals worked just two in every four quarters, both before and after the policy change.

- In the year after the imposition of work requirements, the average quarterly earnings for those who were working were just $5,000. On an annual basis that would be above the federal poverty level for an individual ($11,880), but for the large number who were working only two quarters a year, the wage was still below the poverty line, and well below the income threshold to qualify for food assistance.

In other words, even for the minority whose conditions improved when they met the work requirements, conditions didn’t improve enough to remove the need for food assistance. For most of the Mainers affected by work requirements, the policy meant more hardship — no work and no food assistance.

There are lessons to be found in the Maine data, but they’re not the ones Congress is learning from Rep. Poliquin. There’s nothing to be proud of in Governor LePage’s record on poverty, and Congress is making a mistake by turning to Maine for ideas about how to fight food insecurity.