Contents

Editor’s note: State of Working Maine 2018 contains extensive endnotes and citations not reflected in this online version of the report. To see the complete report in PDF form, click here.

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Good Jobs Provide a Living Income

- Chapter Two: Good Jobs Bring Stability to Workers’ Lives

- Chapter Three: Good Jobs Support Mainers’ Well-Being

- Chapter Four: Good Jobs Provide for a Dignified Retirement

- Chapter Five: Good Jobs Don’t Discriminate

- Chapter Six: Good Jobs Give Workers a Voice

- Conclusion: Good Jobs, Secure Families, Thriving Communities

Downloads

Introduction: Mainers Need Good Jobs Now

Mainers like to work hard and maintain their independence. Doing so means being able to find and keep good jobs that make it possible to comfortably afford the basics, cover emergency expenses, and save for the future.

But this basic understanding of how the economy should work is under threat.

Despite low unemployment and recent economic growth, too many Maine workers and families struggle to make ends meet. Middle-class jobs have disappeared in large numbers and are being replaced by low-wage jobs with greater uncertainty. Income gains are limited or nonexistent for a significant share of Maine workers, while women and people of color continue to earn less than white men.

Faced with these realities, many Maine workers are voting with their feet.

A lack of good jobs and community supports in rural Maine has contributed to an exodus of people to the state’s more urban areas or beyond our borders. Every year from 2011 to 2015, a net 1,700 Mainers moved from rural Maine to the Greater Portland area, while a net of 2,200 residents left the state entirely, primarily for job opportunities.

Labor force participation rates have gone down among working-age Mainers, who are often unable to find a good job or suffer with declining health. Critical worker shortages are becoming a growing concern for employers and the people who rely on the services they provide. Meanwhile, older Mainers struggling to establish a secure retirement are remaining in the workforce longer.

A rising tide should lift all boats, but where our economy is concerned, this has not been the case. The gains of recent economic growth have been unevenly distributed and too many families are finding it harder to get by despite having work.

Too often, work pays too little, is too unpredictable, and doesn’t promote worker well-being. This comes at a cost to all of us in the form of greater inequality, greater demand for public services, and is a drag on the economy.

Mainers can build an economy that delivers on the promise of good jobs. Doing so will improve quality of life for workers, but it will also create a stronger economy.

When jobs pay higher wages, workers spend that money on groceries, health and child care, and other local goods and services. When workers have better access to affordable, quality health care, they are more productive. When workers have stable employment, they can strike a work-life balance that allows them to pursue higher education or otherwise improve their job prospects. All of these factors would kick-start a more dynamic, inclusive economy.

As workers, employers, and citizens, all Mainers have a stake in creating an environment in which economy-boosting jobs that sustain families are the norm.

It is time to get back to the fundamentals of what makes a good job and to recognize the role that lawmakers, government officials, and policy can play in building an economy that results in better outcomes for all, not just those at the top of the income ladder.

What makes a “good job?” There are five basic components.

- A good job:

- Pays a livable wage

- Provides stable and secure employment

- Promotes workers’ health and well-being

- Provides for a stable and dignified retirement

- Is accessible to anyone qualified and able to work

How do we create and maintain good jobs?

Part of the solution lies with employers, who recognize that providing good jobs for their employees is good for business. But without a level playing field, employers who strive to provide good jobs can be put at an unfair disadvantage by those who do not.

Part of the solution lies with policymakers, who play a role in ensuring all workers benefit from basic protections. Policymakers must enact and guarantee proper enforcement of workplace laws and regulations and make sure that public dollars are spent to promote economy-boosting, rather than economy-busting, jobs. This is especially true for jobs in government, education, and health care, where most or all of workers’ wages come from public sources.

And finally, part of the solution lies with workers, especially worker unions. When workers organize to build the power to negotiate improvements in their working conditions, they improve both their own workplaces and the economy at large. Declining union representation means more workers are being left behind.

In the pages that follow, the Maine Center for Economic Policy evaluates the basic components of good jobs and identifies specific policy solutions that will ensure such jobs are available to Maine workers. These solutions represent a starting point and are primarily focused on state-level action that would help level the playing field for workers and employers. These should be pursued in combination with action at the federal level and with efforts to boost education and training and to strengthen worker protections.

All Mainers participate in our economy and deserve a voice in setting the terms of that participation. Mainers demonstrated their ability to influence the rules and outcomes of our economy when they passed the minimum wage referendum in 2016. This one change has helped lift thousands of families and children out of poverty and has generated other benefits for the broader economy.

The 2018 State of Working Maine provides recommendations that will help build an economy that truly lifts all boats and delivers on the promise of good jobs, secure families, and thriving communities.

Chapter One: Good Jobs Provide a Living Income

A clear indicator of a job’s quality is the income it provides. At a minimum, a good job should pay enough to enable workers to provide for themselves and their families.

But far too many workers’ paychecks are too small to do this. Four in ten Maine households earns less than a living wage, defined as the pay rate necessary to cover the basics, such as food, housing, transportation, and health and child care. The situation is even worse for households with children or seniors. Inequity in pay for women and people of color makes a difficult situation harder still for historically oppressed groups.

For some workers, low pay is not the only problem. Wage theft takes money out of workers’ pockets, leaving some low-wage employees earning less than the minimum wage and many more with paychecks that underrepresent their actual work. Meanwhile, outdated and difficult-to-enforce overtime protections mean many workers are stuck with lower wages even if they’re willing or required to work more than 40 hours per week.

Any agenda to promote economy-boosting jobs must begin with living wages for all workers — regardless of gender or color. Policymakers have an opportunity to promote income security by updating the state’s wage and hour regulations to guarantee workers’ incomes and reflect the realities of the modern workplace.

Living Wages

Good jobs pay workers enough to support themselves and their families.

All Mainers — white, black, and brown — want to earn enough to support themselves and their families. While every family is unique, there are certain basics that provide a decent standard of living: food, housing, transportation, health and child care, as well as other items such as clothing and household supplies.

A team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has calculated the cost of these items for families in every state, based on family composition and local prices. This “living wage” is a more accurate representation of a family’s basic income needs than the federal poverty level, which hasn’t been updated since 1963. This out-of-date official poverty threshold underrepresents the true state of poverty in the United States.

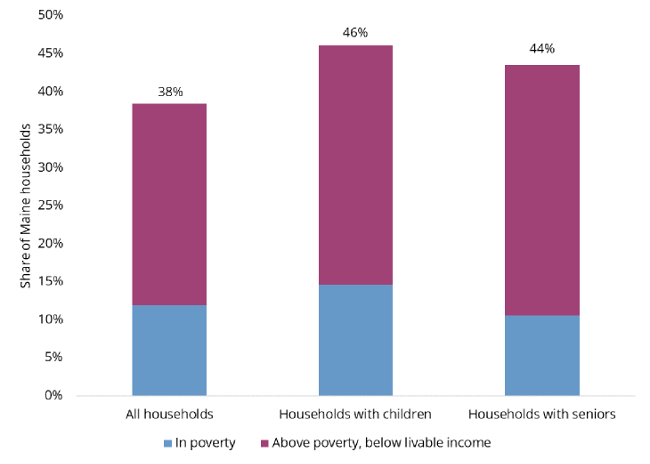

While just 12 percent of Mainers live under the official federal poverty level, far more struggle to make ends meet. Under MIT’s measure, 38 percent of Maine families don’t earn enough to pay for the basics. That’s more than one out of every three families in Maine (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: More than one in three Maine families don’t have livable incomes

MIT’s calculation of a living wage for Mainers is between two and three times the official federal poverty level, depending on family composition. That analysis indicates that many Mainers who earn more than the official poverty level are ineligible for anti-poverty programs but nevertheless struggle to make ends meet. The situation is especially acute for the most vulnerable Mainers, such as children and seniors. Nearly half of households containing children (46 percent) or seniors (44 percent) don’t have a livable income.

Too many Mainers work in jobs that don’t pay enough to support a family. In 2017, more than one in four Mainers (28 percent) worked in jobs paying less than $11.60 per hour — the livable hourly wage for a single adult as determined by MIT. Maine’s 2016 minimum wage law, which will raise the minimum hourly wage to $12 by 2020, will likely increase the number of jobs paying a livable wage, but there will still be many Mainers whose jobs don’t support a basic standard of living. In two-parent households, each parent must earn at least $15.82 per hour to adequately support two children. More than half of Mainers earn less than that rate today. Many of those will continue to earn less than a living wage even after the full $12 minimum wage is implemented.

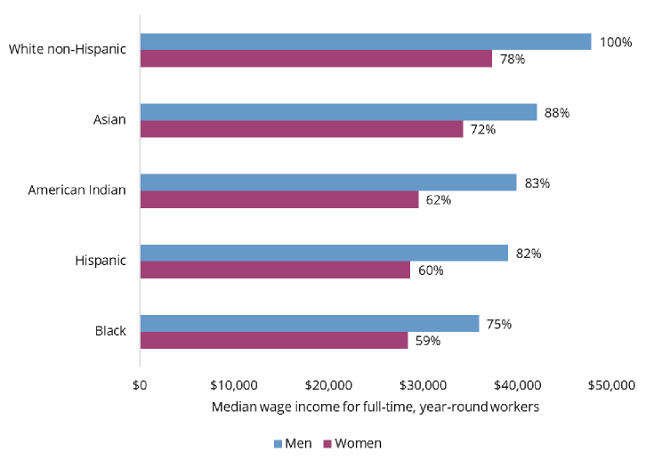

Figure 2: Mainers face significant gender and racial pay gaps

The number of Mainers who work but still cannot afford to keep food on the table also demonstrates inadequate wages.

The share of Maine workers who are food-insecure is on the rise. Today, one in ten private-sector wage and salary workers in Maine are food insecure, meaning they do not have access to enough food or to nutritious food. In 2006, the rate was one-in-fifteen. Workers in some sectors are even more likely to be food insecure: Hunger or the risk of hunger is a constant stressor for one in four health care support workers, one in eight food preparation or service workers, and one in eight building and grounds cleaning and maintenance workers.

Improvements to worker compensation in Maine must also address the wage inequity that sees women and people of color earn less than white men. Gender and racial wage inequity exist among workers within the same industries even when those workers have the same qualifications and experience. Those lower wages perpetuate inequity, as women and people of color are less able to build wealth than their white male peers.

In Maine, the median wage for a white woman working full-time is just 78 cents on the dollar compared with a white man on the same schedule. This gap is even wider for people of color working in Maine (See Figure 2).

Policy Solutions:

Continue to boost the minimum wage: Current Maine law will index the minimum wage to inflation after 2020, when it reaches $12 per hour, ensuring that its value is not eroded by the increased cost of living. However, he minimum will remain below a living wage for many Mainers. Absent federal solutions, state lawmakers should continue to implement and monitor scheduled minimum wage increases while considering further increases after 2020, such as a goal of a $15 minimum wage by 2026. Massachusetts will increase its minimum wage to $15 by 2023. An annual increase of 50 cents per hour after 2020 would bring Maine’s minimum wage to $15 by 2026.

Guarantee equal pay: Maine should pass legislation to guarantee equal pay for equal work across gender and race lines. This includes joining other states in prohibiting employers from asking about salary history in job applications, a practice that perpetuates the wage gap for women and racial minorities. California, Delaware, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Puerto Rico have already passed legislation to this effect.

Establish wage transparency: Maine law already prohibits retaliation by employers against employees who share their salary information with co-workers. When workers can compare compensation rates, they can collectively hold their employer accountable for disparities. Maine should join other jurisdictions in requiring large companies to publicly disclose the gap between men’s and women’s compensation. California recently proposed such legislation, and Ontario, Canada, has passed it. Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom recently enacted this policy, which provides more transparency for workers and the public and prompts employers to examine their own workplace practices.

Wage Theft

Wage theft takes hard-earned money out of workers’ pockets. It occurs when employers do not accurately compensate workers for the total number of hours worked. It can come in the form of nonpayment for labor, failure to pay at least the minimum wage, or failure to pay overtime because of illegal misclassification. National studies show that women, people of color, and immigrants are especially vulnerable to wage theft.

Restaurant servers who have ever taken home less than the minimum wage have experienced wage theft. So too have unpaid interns who performed tasks that benefited their employers, but who weren’t compensated for their labor. Employees who drive their own vehicles between job sites but aren’t reimbursed for their mileage may also be victims of wage theft.

Approximately 9,000 Mainers are paid at equivalent hourly rates below the legal minimum wage every year. This illegal underpayment of wages costs these workers $30 million in lost wages annually. This represents just a portion of all wage theft in Maine. An additional, unknown number of workers are paid at rates below their agreed-upon hourly rate above the minimum wage. A 2008 survey of 4,000 low-wage workers in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles found that more than two-thirds of them had suffered some form of wage theft in the past week.

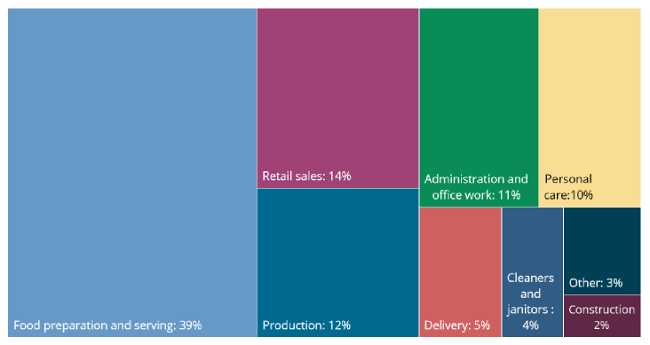

Figure 3: Four in 10 wage theft victims are restaurant workers

Of the 9,000 Mainers who work for an hourly equivalent rate below the statutory minimum wage, four in ten work in the food sector. This includes servers, whose reliance on tips can lead to being underpaid, but also significant numbers of kitchen and other “back of house” staff.

Employers commit wage theft against tipped workers whenever those workers’ take-home pay, including tips and wages, amount to less than the minimum wage for the number of hours they worked. While employers are required to ensure tipped workers earn the minimum wage, the responsibility for tracking hourly pay rate falls to employees. It is difficult for employees to track hours, tips, and wages while performing their job duties. This becomes even more complicated since the timing of when they get their tips and when they get paid can differ by days or even weeks. Additionally, the current system puts the burden on workers to advocate for their full wage. This approach ignores the power dynamics of the workplace and means that many tipped workers, even those who track their hours and pay, remain underpaid.

A 2010-12 investigation of 9,000 restaurants by the federal Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor found that 84 percent of investigated restaurants had wage violations.

The remaining Mainers subjected to wage theft work in a variety of occupations — retail, manufacturing, and office work, for example, as well as personal care and other service industries (See Figure 3).

While many Mainers are victims of wage theft as a result of their employers’ failure to guarantee they earn the minimum wage, many more Maine workers are victims of wage theft as a result of other workplace practices. For example, Maine law requires workers to be paid from the time they arrive at work to the time they leave. Employers who have their employees “clock in” late or “clock out” early are committing wage theft. Wage theft also includes requirements that tipped workers give a portion of their tips to management.

If policymakers do not work to reduce wage theft now, the number of workers subjected to these practices will likely increase. Wage theft is most prevalent in those sectors of the economy forecast to grow over the next decade. Recent and scheduled increases to Maine’s minimum wage increase the likelihood that more workers will be subjected to wage theft. Not only is this bad for workers, it also creates an uneven playing field for those employers who play by the rules.

Policy Solutions:

Strengthen enforcement of workers’ pay protections: Existing worker protections to prevent wage theft are not properly enforced in part because federal and state authorities lack adequate resources. The Wage and Hour Division of Maine’s Department of Labor has just six full-time equivalent positions. Other states similar to Maine in size have much more robust departments; Hawaii has 18 employees, and New Hampshire has 16. Lawmakers should increase funding to the Wage and Hour Division of the Maine Department of Labor for enforcement of minimum wage and overtime laws.

Increase the penalties for employers found guilty of wage theft: Studies have shown that stronger wage and hour laws are effective in deterring wage violations. Maine lawmakers should join five states (Arizona, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Ohio, and Rhod e Island) that have adopted “triple damages” penalties for instances of wage theft, in which employers have to pay three times the back wages owed to employees.

Eliminate the subminimum wage for tipped workers: The tipped minimum wage is difficult to enforce and easily abused, resulting in millions of dollars in lost take-home pay for Mainers every year. Lawmakers should gradually phase out the tip credit, and incrementally raise the subminimum wage until it is equal to the regular minimum wage. Seven states currently have no tip credit and research shows that tipped workers in these states are tipped just as frequently as workers elsewhere and earn higher wages as a result.

Overtime

The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) requires that eligible employees receive overtime pay worth 1.5 times their normal wage for any time worked beyond 40 hours a week. This law was a direct result of organizing by workers in the 19th and 20th centuries.

But the FLSA does not apply to all employees, leaving many workers without its protections. The original law excluded workers in industries where a disproportionate share of the jobs were held by women and people of color. While Congress has addressed some of these exclusions in subsequent changes to the law, persistent pay gaps by race and gender as well as lower prevailing wage rates in certain industries and for certain classes of workers are symptoms of the original law’s discriminatory carve-outs.

In addition, many salaried workers continue to be exempt from the FLSA’s overtime provisions. Salaried workers have traditionally been exempt from overtime protection if they are high-earning and work in professional, administrative, or executive roles. However, it is increasingly difficult to definitively determine whether an employee is truly a “professional, administrative, or executive” worker. This makes the definition of “high-earning” especially important. The current federal definition of a high-earning salaried worker — $23,660 per year — is so low that nine in ten Maine salaried workers are denied overtime pay. This low threshold combined with overly broad categorization of workers as professional, administrative, or executive means that nearly any salaried employee can be classified as exempt from overtime protection.

For those workers who are covered by overtime rules, technology has blurred the distinction between work and personal time. Employers increasingly expect their employees to be available by email and cell phones and to work from home during “off” hours. Two-thirds of Americans note that they are working more after hours than they were a decade before, and workers who frequently check email outside of work are more likely to experience elevated levels of stress. To preserve a healthy work-life balance, overtime protections need to be updated to reflect these realities.

There is insufficient data to determine the prevalence of overtime violations in Maine, but several national studies suggest it is a widespread practice. Nationally, low-wage workers are particularly vulnerable to overtime violations. One survey of low-wage urban workers found that 76 percent of those who worked more than 40 hours a week had their right to overtime violated by their employer. Of those overtime violations that have been investigated and prosecuted in Maine, the industries that accounted for the most violations were health care (32 percent), accommodation (20 percent), restaurants (15 percent), construction (10 percent), and agriculture (6 percent).

Policy Solution:

Provide overtime pay to more workers: Maine should strengthen its existing overtime law to protect more workers. Maine law currently sets the salary threshold for determining exempt status at the annual equivalent of 3,000 times the state minimum wage. With the scheduled increase in the minimum wage to $12 per hour in 2020, the threshold will increase to $36,000 per year. This will lead to increased overtime protections for an additional 12,000 salaried Mainers by 2020.

To truly align the salary threshold with living standards, however, it should be set higher. The 1975 threshold was the equivalent of 70 hours of minimum wage work per week. If Maine pegged the salary threshold at that standard, it would reach $43,680 annually in 2020 and cover an additional 50,000 workers.

Chapter Two: Good Jobs Bring Stability to Workers’ Lives

Predictable, full-time, year-round work gives workers the security of knowing they’ll be able to make ends meet not only today, but into the future. The modern workplace should provide such stability and predictability to any worker who wants it.

In today’s economy, however, that security is harder and harder to find. Mainers work part-time and seasonal jobs at a rate higher than their regional or national counterparts. Nearly one-third of working Mainers work multiple jobs, work only part of the year, or both.

While a large seasonal, weather-dependent tourism sector means at least some seasonal employment is baked into Maine’s economy, unreliable or precarious employment undermines Mainers’ economic well-being and makes it harder to maintain work-life balance.

That balance is even less attainable for the Mainers whose work schedule is unpredictable week-to-week or even day-to-day. For many workers, the scales are tipped in favor of employers who have broad discretion to set workers’ schedules unilaterally and alter those schedules at a moment’s notice.

When workers can have their schedule changed with less than a day’s notice, work-life balance becomes nearly impossible. Without knowing when they’ll be working, Mainers don’t know when they’ll need child care or when they can schedule a doctor’s visit. Further education that could improve job prospects is harder to pursue when workers don’t know whether their work schedule will accommodate classes.

While some portions of Maine’s economy are seasonal, more can be done to mitigate the instability that’s unavoidable in the seasonal economy while also protecting Mainers’ from unnecessary volatility with more robust public policy.

Seasonal Work

Maine’s economy is highly seasonal and many jobs provide only temporary employment for a portion of the year. Seasonal work is especially prevalent in tourism-related sectors, but the phenomenon occurs in other industries as well. The prevalence of seasonal work in Maine presents a challenge to Maine workers because it is inherently unstable.

Many Mainers need to piece together multiple jobs over the course of a year to earn a livable income. Temporary seasonal work also comes with fewer benefits such as health insurance, retirement plans, or paid sick and vacation leave.

Even when Mainers are working the equivalent of a full-time, year-round schedule, they often aren’t receiving the benefits associated with that kind of work because they are working multiple temporary or seasonal jobs.

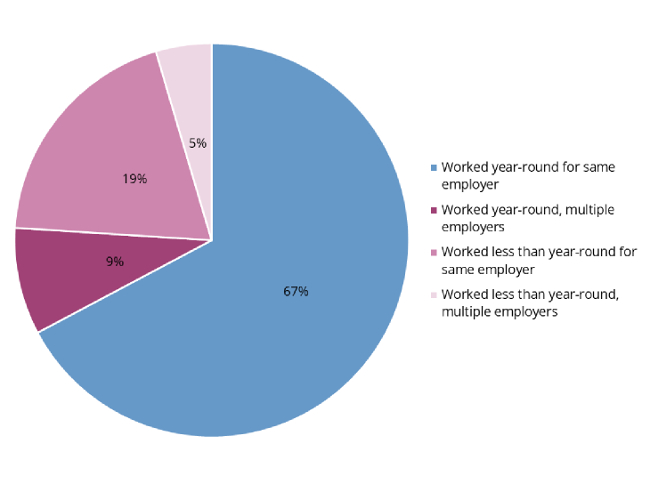

In 2016, one-third of working Mainers did not work year-round at one job (See Figure 4). Around a quarter worked less than year-round, while the remainder worked year-round, but only by working more than one job. The economic situation of these Mainers shows that for many, this is not a choice, but a hardship.

Figure 4: One-third of Maine workers don’t have a single, year-round job

Mainers working less than year-round are nearly five times more likely to be living in poverty than those working year-round for the same employer. And even those Mainers who are working year-round but who had multiple jobs over the course of the year are two-and-a-half times more likely to be living in poverty than someone working the same number of weeks for a single employer.

A large portion of Maine’s seasonal workforce is tied to its tourism industries. Almost one-fifth of Mainers who work less than year-round work in hotels, restaurants, or places of entertainment. Just as many are employed in retail, wholesale, delivery, and warehousing. But there are also significant numbers of education and health care workers who do not work year-round.

Policy Solutions:

Protect and reduce barriers for safety net programs that help stabilize families: While policymakers cannot alter the core conditions that create the need for seasonal work in Maine, they can improve the economic security of workers engaged in seasonal work. Rather than withdraw support for Mainers who can only find seasonal work, lawmakers should make sure programs that can stabilize families — such as unemployment insurance, food assistance, and family support — are readily available to workers between jobs. Lawmakers must reject efforts to impose work requirements, time limits, or other high hurdles that ignore the fact that year-round work in Maine can be hard to find.

Guarantee workplace protections for seasonal workers: Similarly, Maine lawmakers should account for the prevalence of seasonal work when they craft workplace policies. For example, Maine’s Family and Medical Leave statute protects the right to unpaid leave only for Mainers who have been employed with the same employer for 12 consecutive months. This excludes tens of thousands of Mainers who work on a seasonal basis, even those who return to the same employer over multiple years. Lawmakers should ensure that such benefits are available to all workers.

Part-Time Work

Part-Time Work

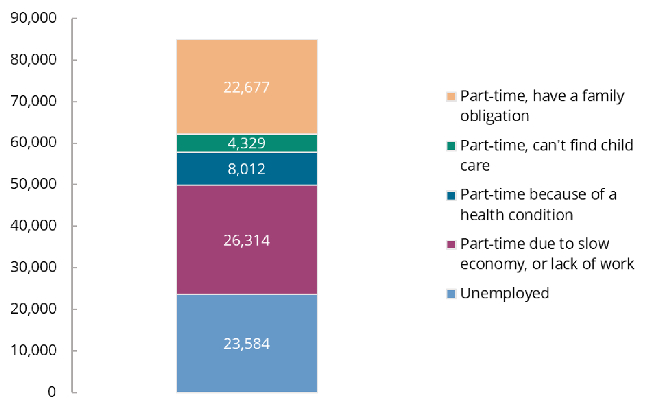

In addition to seasonal work, the prevalence of part-time work in Maine’s economy reduces economic opportunity for many Mainers. On average, a quarter of Maine’s workforce — roughly 180,000 people — worked part-time, defined as fewer than 35 hours per week, in 2017. While some Mainers may choose to work part-time for personal reasons, the inability to find full-time work even when it is preferred causes economic hardship for many workers and families. In 2017, part-time workers in Maine were five times more likely to be living in poverty than full-time workers.

Data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Labor show how difficult it is for Mainers to find full-time work, and why. Of the roughly 180,000 Mainers who worked part-time in any one month in 2017, 26,000 worked part-time because they couldn’t find full-time work or because their hours at work were reduced. For context, that number of underemployed Mainers is larger than the number of Mainers reported as officially unemployed over the same period.

Traditionally, economists only include part-time workers who list business or economic conditions as their reason for working part-time in their determination of who is “underemployed.” However, there are tens of thousands more Mainers who are working part-time for reasons that are caused indirectly by economic conditions and public policy choices. Another 35,000 Mainers are working part-time because of poor health, because they must care for a family member, or because they have trouble finding affordable child care (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: Underemployment plagues tens of thousands of Mainers

A lack of available full-time work for Mainers who want it, combined with often low wages, explains why so many Mainers cobble together multiple jobs to make ends meet. In any given week, 28,000 Mainers were working more than one job in 2017. Even where these Mainers could piece together full-time hours at multiple jobs, they lack the economic security of a single employer and are less eligible for employer-sponsored benefits than their peers working full-time at a single job.

Policy Solution:

Expand access to health care, child care, and home care so that Mainers can work: Tens of thousands of Mainers are underemployed for reasons that can be addressed with public policy. Ensuring Mainers have access to adequate health care coverage, affordable child care, and compassionate elder care services will help remove some of the barriers to working full-time.

Uncertain Schedules

Work should bring stability to employees’ lives. A good job financially sustains employees in the present and allows them to plan for the future — whether that means saving for a rainy day, buying a house, or starting their own business. But for too many Mainers, volatile work scheduling leaves them uncertain about today and anxious about tomorrow.

Workplace volatility can take many forms. Seasonal work, a reality for many Mainers in tourism- or natural resource-related industries, is volatile on a month-to-month, year-over-year basis. Around 28,000 Maine workers are uncertain about their medium-term employment prospects. This includes wage and salary employees who are simply uncertain about their employment prospects, as well as on-call workers, independent contractors on short-term contracts, and other contingent workers.

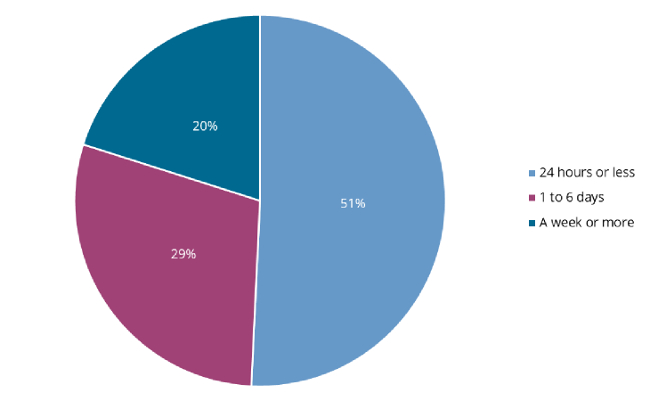

Figure 6: Most Mainers with irregular schedules get less than a day’s notice

Mainers are more likely than other Americans to be working in so-called “contingent work.” The U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent contingent worker survey found that while the share of Americans nationwide involved in contingent work (3.8 percent) had declined from prior years, the share of Maine workers in this situation (4.3 percent) has remained relatively consistent with past surveys.

A more immediate concern for many Mainers, though, is day-to-day scheduling uncertainty that leaves employees unsure how much, or even whether, they’ll be working on any given day.

The practice of on-demand scheduling has grown increasingly common, aided in part by technological advances that have allowed businesses to pinpoint demand for labor. One in five Maine employees (19 percent) works on an unpredictably variable schedule set completely by their employer.

Mainers are slightly more likely than other Americans to have their employer dictate their schedule and Maine employers tend to give their workers less notice of their schedule than the average U.S. employer. Half of Maine employees with irregular schedules — or one in 10 Maine workers — learn their schedule day-by-day, unsure what their workday will look like until the day before (see Figure 6). Another 30 percent learn about their schedule two to six days in advance, and only one-fifth have at least a week’s notice of their work schedules.

On-demand scheduling comes at a cost to workers and businesses. In addition to having erratic incomes, workers with unpredictable schedules have trouble managing elder and child care, and with planning other aspects of their lives outside of work. They are also more likely to suffer from a range of health problems, from fatigue to stress and digestive issues. This can lead to a downward spiral for workers — irregular hours make them sicker and make it harder for them to schedule child care, both of which undermine their availability and productivity and may result in increased employee turnover.

Policy Solutions:

Guarantee fair scheduling for workers: Maine lawmakers should adopt fair scheduling laws such as those recently passed in Oregon as well as several cities, including New York, San Jose, Seattle and San Francisco. Provisions of fair scheduling laws include a minimum notice period for scheduled hours and/or additional pay for on-call work and last-minute schedule changes; requirements that existing staff are offered extra hours before new staff are hired; and guaranteed minimum time off between shifts.

Chapter Three: Good Jobs Support Mainers’ Well-Being

A healthier workforce is a more productive workforce. But too many Mainers lack access to even a single paid sick day, or to paid family and medical leave that allows them to care for newborn children or ailing parents. This lack of access undermines the well-being of Maine families and hits the brakes on Maine’s economy.

Everyone gets sick. Nearly everyone will, at some point, confront life-changing circumstances such as the birth of a child or the death of a parent. These experiences are shared by all people, regardless of their background.

No one should lose their job or suffer lost income because they fall ill. And no one should have to prematurely rush back to work after the birth of a child or death of a loved one.

Access to paid sick leave is proven to improve workers’ productivity and health and to limit the spread of illness and disease. Family and medical leave allows workers to balance work-life challenges and improves the long-term well-being of families and children. Unfortunately, discrepancies in workers’ access to these and other benefits reinforce existing inequalities and make it harder for low-wage workers to move up the economic ladder.

Beyond paid leave, the link between work and access to health coverage puts low-wage workers and those working in seasonal or part-time jobs at an even greater disadvantage. While more than 60 percent of Maine workers are covered by an employer-sponsored health insurance plan, that benefit is largely reserved for those with year-round, full-time jobs.

Between 2006 and 2017, employer-sponsored health insurance became costlier for employers and employees alike, while deductibles skyrocketed. Employers and employees are all paying more for less coverage and increasingly are choosing to go without.

The fundamental question is whether health coverage should be directly tied to employment. MECEP’s view is that it should not. In the long term, health coverage must be decoupled from work so that all Mainers, regardless of their employment status, can receive quality, affordable health care. This chapter focuses on those policies that are by their nature tied to employment — those that affect workers’ ability to take time off from work to care for themselves and their loved ones.

Paid Sick Leave

Everyone gets sick, but thousands of Mainers are forced to choose between their health and their financial security if they fall ill or if a parent or child gets sick.

The ability of employees to take time off work for their health or the health of a loved one, without fear of retribution or lost pay, is crucial to both worker well-being and economic productivity. But many workers can’t take a single sick day without losing income.

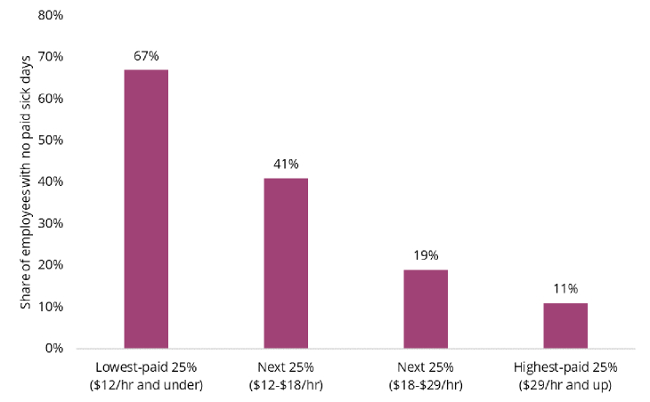

In New England, 22 percent of private-sector workers have no paid sick leave. The share in Maine is likely to be significantly higher; Maine and New Hampshire are the only New England states which have no mandate for employers to offer paid sick leave. One in five Mainers in the private sector works in firms that provide no paid sick, vacation, or holiday time.

Lack of paid sick leave is costly for Maine families. Mainers lose an estimated $115 million in wages from unpaid sick time every year. Losing wages often means going without basic necessities.

For the average low-wage family in Maine, half a day’s wages is the equivalent of the monthly cost of prescription medicines. Two days’ wages are almost equivalent to the monthly oil and electricity bill. A week’s worth of missed wages is more than the family’s entire monthly grocery budget.

Access to paid sick leave is also a public health concern. The lack of paid sick leave, especially in the hospitality and health care sectors, is a primary cause for the outbreak of infectious diseases. A 2016 national survey found that 50 percent of restaurant workers come in to work sick, as do 60 percent of those in medical jobs. Workers in both professions are especially likely to spread illness at work.

Evidence shows that mandatory sick leave laws ensure that more people have access to leave, and more people take sick leave. As a result, paid sick leave laws can reduce the spread of flu by up to 20 percent. In the 2017-18 flu season, more than 9,000 Mainers fell sick, almost 1,800 were hospitalized, and 85 died from the disease.

Workers without paid sick leave are more likely to show up to work sick, a phenomenon known as “presenteeism,” but they also are less likely to take care of themselves in other ways. Workers without paid sick leave are three times more likely to forgo medical care for themselves compared to workers with access to paid leave. They are also less likely to seek medical care for their family members. Ultimately, this means worse health for employees and increased costs for employers down the line, when minor illnesses become chronic conditions.

When workers show up on the job sick, they are less productive — either because they are less physically capable of working or because they are distracted by their health problems. Lost productivity as a result of presenteeism costs the U.S. economy more than $27 billion every year.

Half of American workers report having at least one day a year where they were unable to focus on their job; one in five reports being distracted in this way for at least six days a year. This includes people concerned about their own health and people concerned about the health of family members who are sick. Without paid sick days, Mainers cannot take time off to care for a sick child, spouse, parent, or themselves.

Figure 7: Most low-wage Maine workers have no access to sick leave

Distracted workers can also pose an immediate danger to themselves and their coworkers. Workers without paid leave turn up to work sick and distracted and are more likely to be the cause of accidents. For employees, this represents a health hazard. For employers it represents additional costs — in the form of longer absences while workers are recovering from injuries and increased workers’ compensation premiums. Access to paid sick leave reduces the rate of workplace accidents by almost 30 percent.

Women and low-wage workers are especially affected by the lack of universal paid sick leave in Maine. Women are more likely to work in the service occupations that don’t offer paid leave and are also more likely to work while sick, and suffer the consequences of doing so. Low-wage workers are the least likely to have access to paid leave, despite being the workers who suffer from the highest levels of poor health, and therefore the greatest need for time off to recover from sickness.

Policy Solution:

Enact universal paid sick leave: Maine lawmakers should adopt a paid sick leave mandate like those in place in 10 states (Arizona, California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington) and the District of Columbia. This would require employers to offer their full-time employees at least 40 hours of paid sick time annually, pro-rated for part-time workers).

Long-Term Family and Medical Leave

Nearly all Mainers will at some point face extraordinary circumstances that necessitate extended leave from work. From joyous occasions such as the birth of a child to more challenging times such as when a parent or grandparent becomes ill or passes away, Mainers need to be able to focus on their families.

The United States is one of the only countries in the world without a comprehensive paid family leave system. This contributes to the lower life expectancies, poorer health outcomes, and reduced economic opportunities for Americans when compared with citizens of other developed countries.

In New England, 87 percent of private-sector workers don’t have access to paid family leave. Ten percent don’t even have access to unpaid family leave, because they are exempt from the federal Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993.

Maine law has a more expansive requirement for unpaid family leave than the federal law. All Maine employers with more than 15 employees are required to offer 10 weeks of unpaid family leave in every 24-month period. However, the large number of small businesses in Maine means that even this low threshold excludes one-quarter of all workers.

Women suffer more from the absence of a paid family leave system, since they are most likely to be called upon as caretakers. They are also the main, but not sole, beneficiaries of family and medical leave post-childbirth — one of the most frequent uses of the policy.

Lack of paid family and medical leave is one of the reasons American women have some of the lowest labor force participation rates in the developed world. It is also the primary cause of their lower wage rates and lower retirement incomes (see Chapter 1).

The ability to care for a newborn and to recover from childbirth is essential for the well-being of parents, particularly mothers, and their babies. When parents can stay home with a new child, children are more likely to receive vaccinations and to breastfeed for the recommended first six months of a baby’s life. New mothers are less likely to suffer post-natal depression and more likely to be in better overall health.

Many adults also require long-term care at some point in their lives. Every year, 178,000 Mainers provide unpaid care to an adult in Maine, a service that is worth $2.2 billion to our economy. Having a family member as a caregiver is good for the sick individual — it can reduce their likelihood of being admitted to hospital by half and reduce the length of hospital stays for those who are admitted.

But many working Mainers must make the near-impossible choice between earning a living or caring for their spouse, parent, or child. Having a sick relative is a stressful experience under the best of circumstances, but when caregivers are losing income as well, they suffer even more, including in the form of additional mental health problems.

Policy Solution:

Enact universal paid family and medical leave: Maine should lead by establishing a paid family and medical leave program, as six states and the District of Columbia have already done.

Family and medical leave is used for medium- and long-term health conditions that affect workers or their family members. The most common example is pregnancy and the birth of a new child, but family and medical leave is also used by workers who have an ongoing health condition, such as cancer, and by workers with sick family members.

Employees and employers would contribute to a fund through a payroll tax, revenue from which would then be used to reimburse employees a portion of their wages when they need to take paid family or medical leave. The most effective paid family and medical leave programs reimburse up to 90 percent of lost wages for the lowest-paid workers and offer up to 12 weeks of leave annually.

Chapter Four: Good Jobs Provide for a Dignified Retirement

Retirement security is vital to a good job. Unfortunately, the right to peaceful retirement has become elusive for many Maine workers.

Retirement is coming later, when it comes at all, for a sizable population of seniors who cannot afford to retire when they would like. Social Security income alone does not provide an adequate retirement income. Pension plans have become scarce. For these reasons, Mainers have found it necessary to continue working well past the traditional retirement age.

Congress created Social Security as a promise, a universal benefit to ensure workers would have a dignified retirement in their twilight years. But over time, the promise has been broken. Mainers are working longer to supplement meager benefits or so they can delay taking Social Security payments, which increase each year until age 70.

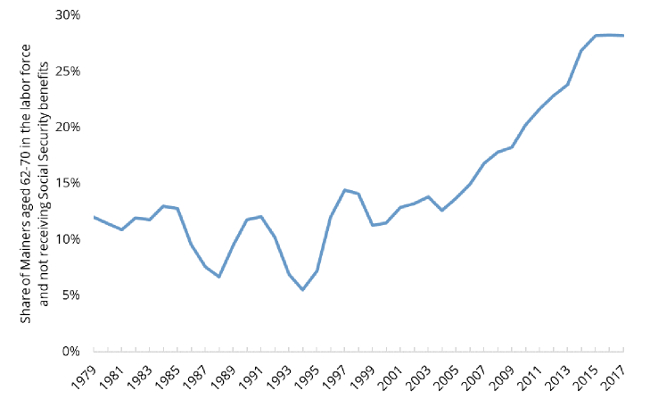

For most of the period between 1977 and 1997, fewer than one in four Mainers between the age of 62 and 70 were in the labor force. By 2017, nearly half of Mainers aged 62 to 70 were working.

The share of older Mainers who were working in order to delay collecting Social Security benefits, and thereby increase their monthly payment, has more than doubled, from 12 percent before 1997 to 28 percent by 2017 (See Figure 8).

Leaders can and must act to bring dignified retirement back within reach for the seniors who have worked hard for decades, and for the younger generation of workers for whom retirement is little more than an unlikely dream.

Figure 8: Mainers are working later in life and delaying Social Security payments

The Retirement Crisis

The crisis in retirement security for Mainers is the result of three factors: the decline in employer assistance for retirement, incomes that are too low for workers to save for their retirement years, and the insufficiency of Social Security payments.

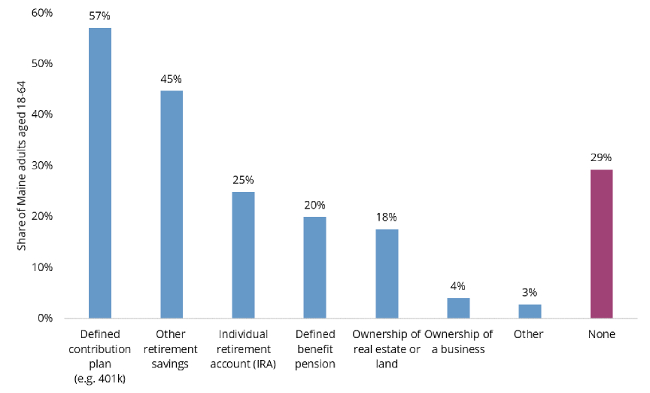

One-third of Maine seniors today have no pension or other non-Social Security retirement income. Moreover, 35 percent of private-sector employees in Maine work for a business that doesn’t offer any contribution to a retirement plan.

This leaves saving for retirement almost entirely to the individual. For low-wage workers, saving for a dignified and stable retirement is all but impossible.

Figure 9: Nearly one in three working-age Mainers has no retirement savings or plan

Social Security makes up the majority of household income for nearly half of Maine seniors, with more than a quarter almost entirely dependent on Social Security income. Social Security lifts millions of American seniors out of poverty, but it provides little more than a subsistence standard of living. Among Maine seniors who receive Social Security, the median payment was just $12,100 in 2017. The federal poverty level in the same year was $12,060.

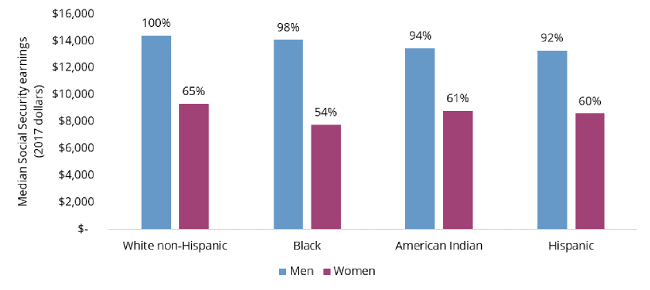

Because Social Security is based on lifetime employment and earnings, payments reflect, and are a result of, gender and race income gaps. Social Security is structured so that low-income contributors receive a larger share of their income as a benefit, which somewhat reduces — but does not eliminate — inequality in benefits.

Women have lower Social Security incomes in retirement because of the gender pay gap and because they are more likely to have missed contribution periods while they were caring for children and other family members. Higher rates of unemployment for people of color, along with discriminatory wages, also contribute to lower Social Security incomes in their retirement.

Figure 10: Inequity in Social Security puts women’s retirement further out of reach

Policy Solutions:

Strengthen federal Social Security: Maine’s Congressional delegation and other leaders should push for improvements to the federal Social Security program. These include developing a new cost-of-living measure for the elderly population, so that benefits more accurately reflect expenses; providing credits towards benefits for people who spend time out of the workforce as caregivers; and eliminating the cap on the payroll tax to bring financial stability to the program.

Implement a state supplement to federal Social Security benefits: Maine should address the inadequacy of federal Social Security payments by supplementing retirees’ incomes with a state benefit. Several states had their own old-age security systems before the enactment of the 1935 Social Security Act. Maine implemented such a system in 1933. A modern state supplement to federal benefits could be achieved with a 7 percent payroll tax, shared between employers and employees, which would pay for an additional benefit of $8,000 a year for Mainers over the age of 65. This would bridge the gap between the median Social Security Benefit and the minimum need of most Maine retirees, as defined by the Elder Economic Security Standard.

Chapter Five: Good Jobs Don’t Discriminate

An economy that shares prosperity begins with shared opportunity.

Previous chapters have described solutions to bring balance to the modern economy, so that work contributes to greater economic security for workers and families. But implementation of those solutions would do little for Mainers who currently face barriers to joining the workforce at all. For these solutions to benefit all workers, barriers that keep certain workers from obtaining and keeping jobs must be addressed.

Workers with criminal histories, the long-term unemployed, and workers with mental health or substance use disorders can be productive members of Maine’s economy. But public and workplace policies and practices, including discriminatory practices, make it harder for these Mainers to obtain and keep jobs.

A strong economy requires more participation, not less. Mainers with criminal records who have served their sentences deserve the opportunity to rejoin society and secure good jobs. Workers who have been out of a job for more than eight months need support re-entering the workforce. Mainers with mental illness or substance use disorders who can work and want to work should be able to do so without discrimination and should have access to the assistance necessary to support their employment.

Criminal History

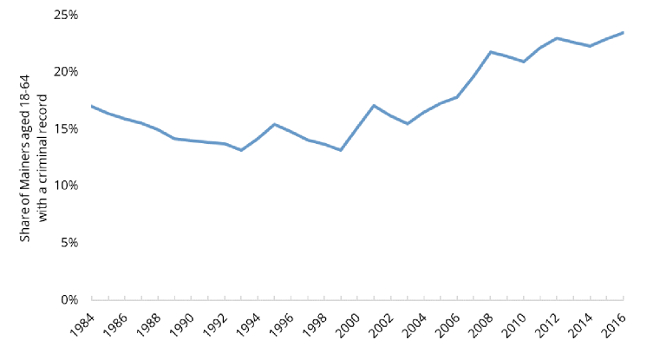

Having a criminal record makes it harder to get a job, which makes it harder to reintegrate into society, and the number of Mainers with a criminal record is on the rise (See Figure 11).

Access to employment is critical to reducing recidivism. A study of Mainers released on probation between 2004 and 2011 found that full-time employment was the greatest predictor of whether a probationer returned to custody within a year of release. Having full-time employment reduced the chances of re-offending by 28 percent.

Maine’s recidivism rate is on par with the national average. The most recent detailed study by Maine Department of Corrections found that 30 percent of Maine’s prisoners “returned to custody” in Maine within three years of release, and that one-tenth returned within the first year of release. This trend increased significantly during the period of study, 2010-2013 (25 percent to 30 percent). Maine’s recidivism rate is four percentage points higher when the data includes individuals released from Maine prisons who are subsequently re-incarcerated in another state.

One solution to reduce recidivism and address a growing demand for workers is to remove barriers that make it harder for those with criminal records to obtain a job. Two-thirds of managers surveyed by the Society of Human Resource Managers, or SHRM, reported that their organization requires reporting of criminal records on initial job applications. Three-quarters conducted criminal background checks as part of the pre-hire screening process.

Figure 11: Roughly one in four working-age Mainers has a criminal record

While the clear majority of those surveyed by SHRM reported a willingness to hire individuals with criminal records, studies show that employers are far less likely to offer a job to ex-offenders than nonoffenders.

A 2009 study by the U.S. Department of Justice found that young, low-skilled ex-offenders were half as likely to receive an interview call-back or a job offer, and that the penalty was much greater for Black applicants (60 percent) than white applicants (30 percent). The Maine State Police does not publish arrest or conviction rates by race in its annual “Crime in Maine” report, but incarceration data show that Black Mainers are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white Mainers.

In 2016, Mainers voted to decriminalize the sale and possession of cannabis. However, large numbers of Mainers still have criminal records based on prior arrests for cannabis offenses, which hinder their ability to work. In 2016 alone, 2,653 arrests were made for cannabis sale or possession, accounting for one in 15 arrests made that year. Black Mainers are twice as likely as white Mainers to be arrested for cannabis possession. Decriminalization provides an opportunity for lawmakers to correct these historic wrongs.

Policy Solutions:

Provide rehabilitation certificates for Mainers who have paid their debt to society: The use of rehabilitation certificates in Ohio has been shown to greatly reduce or eliminate the barriers to employment and housing caused by having a criminal record. These certificates are issued to ex-offenders by a judge as validation that they have paid their debt and are ready to re-integrate into society.

Restrict the use of criminal history in job applications: Maine lawmakers should limit employers’ ability to inquire about applicants’ criminal history. For example, inquiries could be restricted to violent offenses committed within the past five years, or be prohibited from inclusion in initial application materials so that Mainers who have been incarcerated are not shut out from consideration before they even receive an interview. While a growing number of states and cities are prohibiting employers from asking about criminal history in job applications altogether, a movement known as “ban the box,” recent research suggests that in the absence of criminal record disclosures, employers are more likely to resort to racial stereotypes and discriminate more against young men of color. One study of so-called “ban the box” legislation found that it decreased employment among low-skilled young Black men by five percent, and by three percent among young low-skilled Hispanic men. Limiting, without entirely prohibiting, inquiries about criminal histories would give Mainers with a history of incarceration a fairer chance at a job without opening the door to other biases or discrimination.

Expunge outdated criminal records: As Maine voters have made the decision to decriminalize cannabis use and sale, the state should expunge all offenses for simple possession and minor sales. California, Massachusetts, and Oregon have procedures in place to expunge records following legalization of cannabis.

Long-Term Unemployment

Having large gaps on your resume makes it harder to get hired. Mainers of prime working age, between 25 and 54 years old, are increasingly unable to find work because of long periods of unemployment.

Among that age group, 8.9 percent in 2017 had not worked in at least five years, up from 7.5 percent in 2006. Studies show that Americans who have been out of work for as little as eight months are half as likely to find work as someone who has just left a job, and that these differences cannot be explained by characteristics of those workers themselves.

In other words, Mainers who lose their job but are unable to get rehired soon afterwards find it increasingly difficult to get back to work, regardless of their prior experience or qualifications.

Part of this is due to employers’ reluctance to hire people with gaps in their resume, which can amount to discrimination against this class of applicants. But there are also legitimate challenges to hiring the long-term unemployed: Workers’ skills erode over time, which can exacerbate an existing skills mismatch, especially for older workers.

Policy Solutions:

Leverage federal funds to get long-term unemployed Mainers back to work: The federal government provides $8 million in Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act funds for workforce training programs in Maine, but the need is greater than the number of individuals these programs can serve. The state should prioritize spending WIOA funds on intensive training services — and the supports necessary to participate in that training, such as child care and transportation — which provide the most benefit to participants, as well as spending that targets low-income Mainers and the long-term unemployed.

Supplementing federal grants with state funding would also be money well-spent. Research shows that a relatively small cost to the public of $2,000-$4,000 per participant is repaid up to ten times over the course of the worker’s lifetime through tax revenues from increased earnings and decreased use of unemployment insurance.

Mental Health Problems

The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Maine Human Rights Act both protect the rights of workers with mental illness from discrimination at work. Both also require employers to make reasonable accommodations for workers with mental health issues.

However, there is evidence that Mainers with mental illness aren’t being adequately accommodated at work.

But just 27 of Maine’s 209 mental health facilities offer employment support programs, compared to nearly half of New Hampshire’s similar facilities.

Discrimination at work on the basis of physical or mental disability accounts for nearly half of all complaints brought before the Maine Human Rights Commission. The number of complaints on the basis of disability discrimination has more than doubled over the last decade, from 346 in 2007, to 830 in 2017. Mainers with disabilities, including mental health problems, aren’t getting the accommodations they need at work.

Mainers with mental illnesses also find it harder to get hired. They are less likely to be employed and this trend has worsened over the past decade.

Before the Great Recession of 2007, 52 percent of Mainers who reported having frequent days of poor mental health were employed; today that share has dropped to 47 percent. This combined with an increasing share of nonelderly adults who have poor mental health means that there are more Mainers suffering from poor mental health, and they are finding it harder to get work.

While individuals with mental health issues are finding it harder to get and keep a job, work itself is a key driver of mental health. Mainers who work feel more fulfilled and generally have better mental and physical health. Work is also seen as an effective remedy for some people suffering from mental illness.

There are two subsets of Mainers with mental health problems. One group includes Mainers suffering from stress, depression, anxiety and other relatively “low-level” disorders. The other group consists of those Mainers who have been diagnosed with a “serious mental illness,” defined as “serious functional impairment” from a diagnosed illness such as major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.

Around five percent of Maine adults have a serious mental illness, slightly more than the national rate of four percent. These Mainers require more assistance in their work lives, but work is no less important to improve their mental health status. While two-thirds of Americans with a serious mental illness report they want to work, far fewer find employment. Maine is particularly lacking in this regard. Just 9 percent of Mainers served by Maine Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services were working in 2017, less than half the national rate.

Policy Solutions:

Increase education and outreach to employers to ensure accommodations for workers with mental illness: For the larger number of Mainers with less serious mental health concerns, the Department of Labor should ensure that all employers are educated about their responsibilities under the Maine Human Rights Act and the Americans With Disabilities Act. Likewise, Mainers need to be made aware of their rights to reasonable accommodation under both acts. The state must also ensure adequate funding for the Maine Human Rights Commission to tackle its increased caseload.

Expand supported employment: For those with serious mental illness, Maine must provide more opportunities for supported employment. Supported employment programs are proven to be very successful in helping people with serious mental illness reenter and stay in the workforce, but there is a widespread shortage of available program spaces. Just 27 of Maine’s 209 mental health facilities offer supported employment programs, compared to nearly half of New Hampshire’s facilities. Only 74 Mainers receive supported employment services in each three-month period. The Legislature should require that most or all facilities offer supported employment services, and ensure that MaineCare reimbursement is available for all service providers.

Chapter Six: Good Jobs Give Workers a Voice

Good jobs aren’t only built through employer decisions and public policy. Workers also have a role to play in transforming working conditions. But workers can play a role in shaping good jobs only if they have the power and ability to negotiate collectively with their employers.

For that to happen, Maine workers need to be able to easily form unions if they so choose.

Workers have traditionally been empowered through labor unions and it is through unions that Americans have secured higher wages, safer working conditions, and better benefits. The existence of strong labor unions benefits not only union members, but all workers. Stronger unions have been shown to reduce income inequality, promote gender equity, and improve pay and conditions even for nonunionized workers.

Restoring the ability of Mainers to unionize and ensuring that workers are empowered to negotiate their own working conditions is crucial to fostering good jobs in our economy.

Maine, like the rest of the country, has seen a steep decline in union membership over the past half-century. Since 1964, union membership in Maine has halved, from 24 percent of workers in 1964 to just under 12 percent in 2017. These declines have occurred almost exclusively in the private sector, where union membership has fallen from 14 percent in 1983 to just over five percent in 2017. Meanwhile, public-sector union membership has remained at roughly 50 percent over that period.

The U.S. has one of the lowest union membership rates among developed nations. The share of the workforce that is unionized is twice as high in the United Kingdom and Canada, while in some European countries more than two-thirds of workers belong to labor unions.

Researchers attribute some of this decline to a shift in work away from manufacturing jobs, which were traditionally heavily unionized, to service-sector work, where unions are less common. However, there is also considerable evidence that corporations and some lawmakers have been successful in suppressing union membership through legislation and workplace practices that are hostile to union formation and collective bargaining.

The Case for Unions

Fairer Wages and Better Benefits

When unions are strong, their members earn better wages, even after accounting for age, education, occupation, and other factors. Nationally, membership in a union boosts wages by 15 percent, or an extra $1.25 per hour. People of color and workers with fewer credentials gain the most from union membership. Historically, labor and civil rights leaders recognized the positive effect unions had on wage equity. Civil rights leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. fought against so-called “right to work” laws, recognizing the harm they would cause to people of color.

When employers and employees negotiate wages collectively and transparently, wage levels are set more fairly and equitably. While unionized workers still face gender and racial pay gaps, these inequities are significantly smaller for unionized workers than for the rest of the workforce. In Maine, both the racial and gender equity gaps are lower for unionized workers than they are for nonunionized workers (See Figure 12).

Figure 12: Unionized Mainers experience less gender and racial pay inequity

Likewise, Americans in unions are more likely to have paid sick days and paid vacation time, and to have greater control over and more notice of their work schedules. Workers in unions are more likely to have access to defined benefit pension plans. In other words, unions have allowed workers to achieve or maintain many of the good job standards outlined in this report.

Unions Support a Fair Economy, Even for Nonunion Workers

Unions don’t improve wages and working conditions only for their members. When unions are strong, wages and benefits negotiated by unions become standards for entire industries and sectors.

When unions are strong, and workers are better able to negotiate their wages and working conditions, the gains of economic growth are distributed more fairly. A recent study that examined union membership rates going back to 1936 found that the decline in union membership over the past half-century has contributed significantly to the growing income inequality between the poorest and wealthiest Americans.

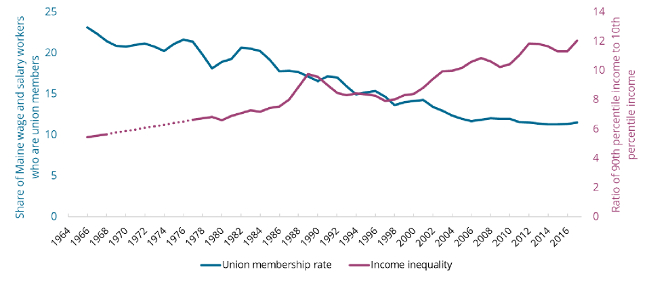

Likewise, in Maine, as union membership has declined, inequality has increased rapidly. Since 1964, as union membership in Maine has halved, the income of the wealthiest 10 percent of Mainers has gone from being five-and-a-half times the income of the poorest 10 percent to more than 12 times the income of the poorest. In other words, the scale of income inequality has more than doubled (See Figure 13).

Figure 13: Income inequality has risen as union membership has declined

Growing income inequality is a moral and an economic problem. It is fundamentally unfair that a greater share of the growing economy to which we all contribute is being captured exclusively by a small slice of the population. What’s more, the growth of income inequality in the United States is hollowing out the middle class and slowing economic growth. As low-income Mainers are less able to benefit from economic growth, they are more likely to be trapped in poverty and less able to make it into the middle class. Middle-class families are the foundation of a strong economy. Their purchases of goods and services drive demand and spur growth. As more income is captured by the top earners, there’s less ability for the middle class to spend money on these products and less reason to create jobs to meet demand.

Unions play a central role in rebalancing our economy and ensuring that workers benefit fairly from the results of their hard work.

Anti-Union Activities Hurt Workers

Unions are good for workers and the economy but union membership has declined precipitously over the past few decades.

It’s not because Americans are fundamentally opposed to unions. In fact, 62 percent of Americans have a favorable opinion of labor unions. This represents the highest level of approval in 15 years, and close to historic high levels of support.

Union membership has declinined because of opposition from employers, not average Americans. While support for unions has been growing among most Americans, employers continue to actively oppose worker organizing. These efforts have included public statements, legislation in State Houses and Congress, and lawsuits designed to weaken unions and the protections they afford to workers.

Employers sometimes engage in unfair or illegal practices to prevent workers from unionizing. Studies show that this activity is becoming more common. A study of union elections between 1999 and 2003 found that in two-thirds of elections, employers required workers to attend one-on-one sessions with their supervisors to discourage organizing. In more than half of cases, employers threatened to close the plant if workers organized. In half of cases, employers threatened to cut wages or benefits and in more than one-third of cases, employers threatened layoffs if workers organized. The same study also showed that such tactics had increased significantly over the preceding 20 years.

Policy Solutions:

Increase penalties for employers who suppress worker organizing: Lawmakers must protect workers’ right to unionize and crack down on employers who retaliate against workers who try to organize. Maine should pass legislation based on the federal proposal known as the WAGE Act, which would increase penalties for companies that interfere with workers’ right to organize and increase the avenues of redress for workers whose rights have been violated.

Establish wage boards to set pay and benefit standards across entire industries: Maine should establish wage boards to bring together workers, business, and government officials to collectively set wages and standards across industries and sectors. These boards, which are common in Europe, already exist in California and New York. In setting consistent minimum standards across an entire industry, wage boards prevent a “race to the bottom” among employers. This process of collective bargaining is like the process used by National Football League teams to set minimum pay rates for all players, regardless of which team they play for.

Restore workers’ rights to free association: The right to join a union is a matter of freedeom of association — a core, protected Constitutional right. But too often employers who oppose union organization suppress that right. The organizing process should be simple: If workers want to form a union, they should be able to do so free from the intimidation, stall tactics, threats, or retribution from employers that are all too common. Unfortunately, years of anti-worker rulemaking, policy changes, and judicial rulings have corrupted the process of union formation. Employers have far too much leeway to stymie their workers’ rights. The federal National Labor Relations Act must be updated and modernized with provisions such as card-check, which would allow workers to form a union through a simple majority sign-up process, rather than the current ballot process controlled by employers.

Conclusion: Good Jobs, Secure Families, Thriving Communities

Mainers want an economy that delivers on the promise of good jobs, secure families, and thriving communities.

It is time to get back to the fundamentals of what makes a good job and to recognize the role that public policy can play in building an inclusive economy that results in better outcomes for all Maine families and communities. Doing so requires policymakers to appreciate the challenges that far too many hardworking Mainers face and to take actions that result in work arrangements that pay enough to support families, are more predictable, and are more likely to promote worker well-being now and in the future.

This year’s State of Working Maine lays out a worker-focused agenda to build an environment in which economy-boosting jobs that sustain families are the norm. This agenda can level the playing field between employers who already succeed at providing good jobs for their employees and those who fall short. It can put workers in a better position to provide for their families and to negotiate improved working conditions. It can create an economy that is better for workers and give Maine a competitive advantage when it comes to attracting and retaining hardworking families in the state.

Mainers know that a rising tide should lift all boats. It is possible to build an economy that does just that. Maine’s economy is growing. The State of Working Maine 2018 provides a blueprint to assure that working Mainers benefit from that and future growth. It provides a blueprint to assure that we all rise together.